Conversations about the future of oil and gas markets often center on demand, how fast renewables will scale, whether policy will constrain consumption, or how economic cycles shape usage. Far less attention is given to supply, particularly the natural decline of production from existing fields. The International Energy Agency (IEA) warns these declines are accelerating and pose a fundamental risk to future supply stability.

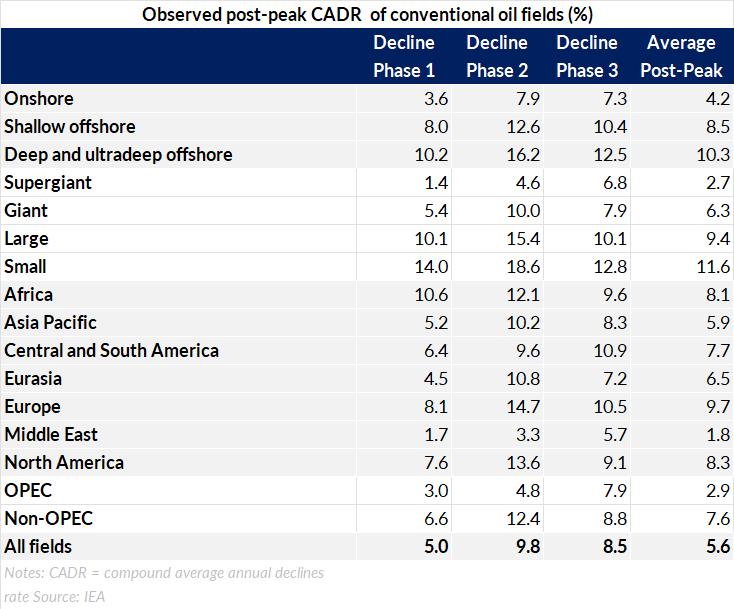

According to IEA analysis, conventional oil fields lose an average of 5.6% of production each year once they peak, while gas fields decline even faster at 6.8%. Decline rates vary sharply by field size. The IEA defines supergiant fields as holding more than 5 billion barrels of recoverable reserves, and notes they decline at just 2.7% annually. Giants (500 million to 5 billion barrels) average 6.3%, large fields (100–500 million barrels) fall 9.4%, and small fields, with less than 100 million barrels, drop by 11.6% a year. The Middle East, home to many of the world’s largest onshore supergiants, shows the lowest decline rates at under 2%, while Europe, where offshore fields make up much of production, faces declines closer to 10%. The IEA also highlights the sharper risks associated with unconventional resources. If reinvestment stopped, US shale output would fall by more than a third in a single year, followed by another 15% drop the next. By contrast, conventional supergiants in the Middle East and Russia could sustain steadier flows.

Phase 1: From peak to when production falls below 85% of the peak level.

Phase 2: From the end of Phase 1 to when production drops to 50% of the peak level.

Phase 3: From the end of Phase 2 to the last year with a material level of production which is generally the final recorded year, or when production drops below 5% of the peak level

Without reinvestment, the IEA estimates global oil supply would shrink by about 5.5 MMBbl/d each year, the combined output of Brazil and Norway, while gas would fall by 270 bcm (~9.5 Tcf). Holding today’s output steady through 2050 would require more than 45 MMBbl/d of new oil and 2,000 bcm (~70 Tcf) of gas from projects not yet built. The IEA notes that although 230 billion barrels of oil and 40 tcm (~1,410 Tcf) of gas have been discovered but remain undeveloped, mostly in the Middle East, Eurasia, and Africa, a large gap persists. Even if these resources were developed, the world would still need annual discoveries of 10 billion barrels of oil and 1 tcm (~35 Tcf) of gas, only slightly above recent trends.

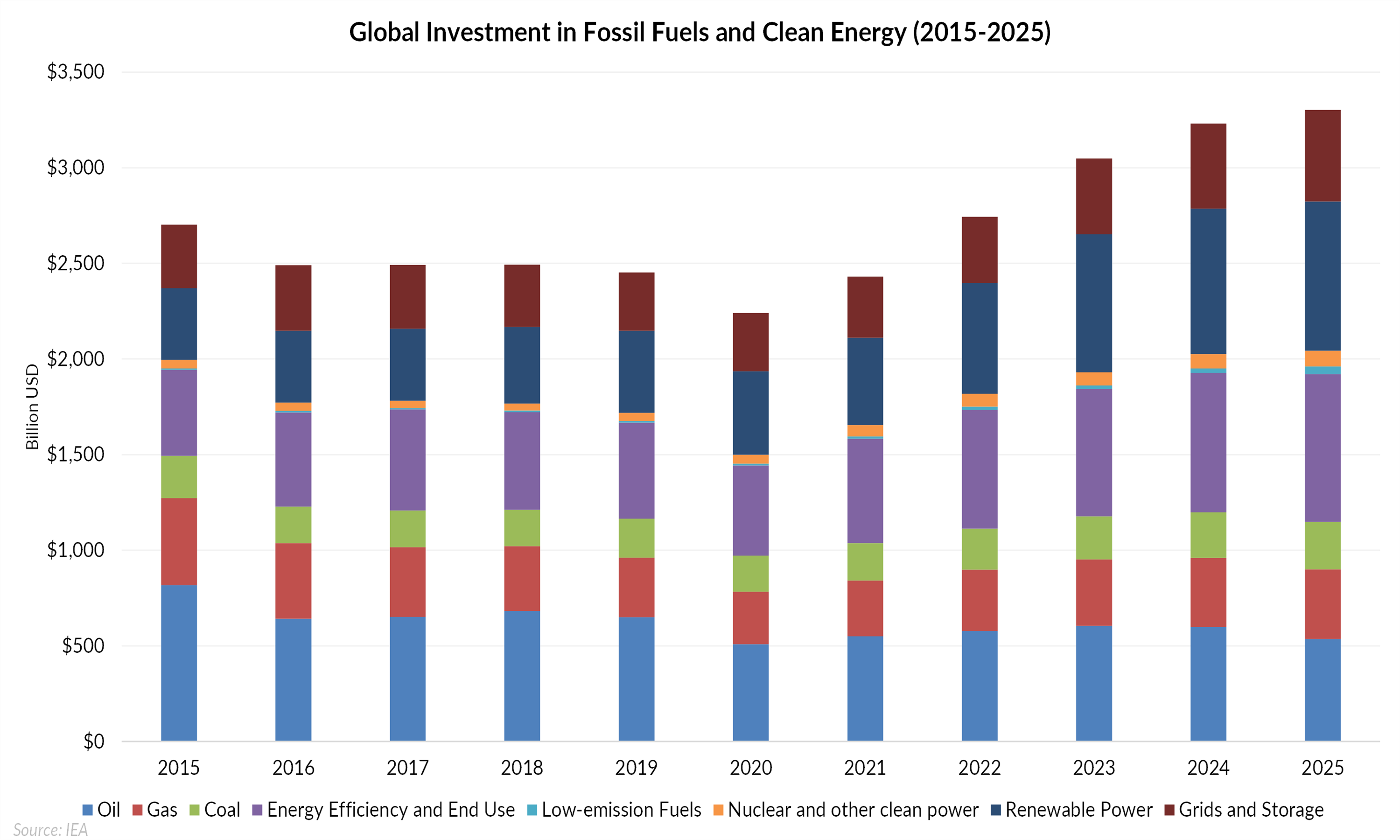

Investment patterns underline the challenge. IEA data show that global spending is rising, yet much of the growth targets clean energy rather than upstream oil and gas. Oil and gas still command significant capital, but not enough to counter accelerating declines. And with new conventional projects taking nearly 20 years from licensing to first production, today’s decisions will shape supply in the 2040s and beyond.

Decline rates are not a distant, theoretical challenge but a near-term reality that requires constant reinvestment just to keep production flat. Economies reliant on shale production face particularly sharp risks if drilling slows, while producers in the Middle East benefit from slower-declining conventional assets. The challenge now is that the majority of investments are no longer driving growth but merely sustaining existing output against accelerating decline rates. The greater vulnerability may not be weakening demand, but a scenario where investment falls short of what is needed to offset the natural erosion of field productivity.